🔴 CRITICAL WARNING: Evaluation Artifact – NOT Peer-Reviewed Science. This document is 100% AI-Generated Synthetic Content. This artifact is published solely for the purpose of Large Language Model (LLM) performance evaluation by human experts. The content has NOT been fact-checked, verified, or peer-reviewed. It may contain factual hallucinations, false citations, dangerous misinformation, and defamatory statements. DO NOT rely on this content for research, medical decisions, financial advice, or any real-world application.

Read the AI-Generated Article

Abstract

Topology optimization can produce heat exchanger cores with superior thermal–hydraulic performance relative to conventional channel layouts. Yet, designs obtained under purely physics-based objectives often contain overhangs, enclosed voids, and unsupported internal features that are impractical to fabricate using laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) without excessive support structures, degraded surface quality, or infeasible post-processing. This article presents a manufacturability-embedded topology optimization framework for additively manufactured heat exchangers that directly incorporates build orientation and support-structure requirements into the optimization formulation. The approach combines (i) a density-based topology optimization model for conjugate forced convection using a Brinkman penalization of momentum and interpolated thermal properties, (ii) a differentiable, orientation-dependent “printability” operator inspired by additive manufacturing (AM) filters for enforcing self-supporting geometries, and (iii) an outer-loop build orientation selection strategy that exposes the trade space among thermal resistance, pressure drop (or pumping power), and required supports. Representative numerical case studies demonstrate that the proposed constraints prevent unprintable down-facing features while preserving much of the topology optimization benefit; compared to unconstrained designs, the constrained solutions typically incur modest thermal–hydraulic penalties while achieving substantial reductions in estimated support volume and support-contact area. Implementation details are provided, including adjoint sensitivities, continuation schemes, and practical LPBF-oriented constraints such as minimum length scale and powder removal access. The resulting methodology enables researchers to generate heat exchanger geometries that are both thermally efficient and manufacturable under explicit build orientation constraints.

Index Terms —topology optimization, additive manufacturing, heat exchangers, design for manufacturing, thermal management, laser powder bed fusion, build orientation, support constraints.

Introduction

Compact heat exchangers underpin a wide range of energy conversion and thermal management systems, including aircraft environmental control, power electronics cooling, fuel processing, and recuperation in advanced cycles. Their performance is typically judged by competing metrics: heat transfer effectiveness (or thermal resistance), pressure drop (or pumping power), mass/volume, and reliability under mechanical and thermal loads. Traditional design approaches—parametric channel families, repeated fins, and empirically tuned manifold layouts—benefit from decades of correlation development and manufacturing know-how [13], [14], but they also restrict the reachable design space. In contrast, topology optimization offers a systematic route to discover non-intuitive flow and heat transfer architectures by distributing solid and fluid regions within a design domain to optimize a prescribed objective subject to constraints [1], [2].

For thermo-fluid systems, topology optimization has matured from Stokes-flow channel problems [3], [4] to coupled convection–diffusion and conjugate heat transfer formulations. However, a persistent barrier remains: when the optimization ignores manufacturing constraints, the resulting geometries can be unbuildable, especially for additive manufacturing (AM). LPBF, in particular, imposes constraints on overhang angles, internal supports, powder evacuation, minimum feature sizes, and orientation-dependent quality (surface roughness, distortion, and local overheating) [9]-[11]. These constraints strongly interact with the heat exchanger problem: high-performing designs often introduce thin, down-facing walls, internal cavities, and tortuous channels that trap powder or require supports that cannot be removed.

Recent research has proposed incorporating AM constraints directly into topology optimization, rather than enforcing them as a post-processing step. Two influential lines of work include (i) explicit overhang/self-support constraints that penalize unsupported regions [8] and (ii) AM “printability” filters that enforce support-propagation conditions along a build direction [7]. These methods were developed primarily for structural problems; extending them to heat exchangers introduces additional modeling complications: the “solid” is simultaneously a load-bearing skeleton and a heat conduction path, while “fluid” regions determine advection, pressure loss, and local heat transfer coefficients.

This paper addresses these challenges by presenting a technical solution tailored to additively manufactured heat exchangers: a topology optimization formulation in which build orientation constraints are embedded as first-class constraints alongside thermo-fluid objectives. The central idea is to treat build orientation as a parameter (and, optionally, a discrete design decision) that defines an orientation-dependent manufacturability operator. This operator maps a candidate density field into a “printable” density field consistent with support requirements in LPBF; the topology optimization is then constrained such that the design is self-supporting (or support-limited) for the selected orientation.

Contributions

The main contributions are as follows:

-

Orientation-dependent manufacturability operator for thermo-fluid topology optimization: We adapt AM filter concepts to a conjugate forced-convection topology optimization setting, yielding a differentiable support surrogate and a direct build orientation constraint.

-

Unified multi-constraint formulation: The optimization simultaneously manages thermal resistance, pressure drop (or pumping power), material usage, and a support/self-support constraint tied to the LPBF build direction.

-

Implementation-level guidance: We provide adjoint sensitivity expressions (at the level needed for implementation), a continuation strategy for projection and penalization, and a practical outer-loop orientation selection strategy.

-

Representative validation studies: We report illustrative numerical case studies comparing unconstrained and manufacturability-constrained heat exchanger cores, including a build-orientation trade study and qualitative verification against higher-fidelity CFD on post-processed designs.

Scope and Limitations

The framework targets LPBF of metallic heat exchangers, emphasizing build orientation and support requirements. Other AM realities—residual stress distortion, microstructure anisotropy, and roughness-induced pressure losses—are addressed as discussion points rather than fully coupled process–property models. Where evidence is limited or highly machine/material dependent, we explicitly treat these aspects as uncertainty sources rather than settled facts.

Illustrative representation (author-generated): A schematic showing (a) a rectangular heat exchanger design domain with inlet/outlet manifolds, (b) a build platform with a highlighted build direction vector b , and (c) examples of down-facing surfaces requiring supports under one orientation but not another.

Design/Method

Physical Problem Definition

We consider a compact heat exchanger “core” represented by a fixed design domain ![]() containing both fluid and solid regions. In a single-fluid, single-solid formulation, the design variable

containing both fluid and solid regions. In a single-fluid, single-solid formulation, the design variable ![]() indicates the local material state:

indicates the local material state: ![]() corresponds to solid (high conductivity, low permeability), and

corresponds to solid (high conductivity, low permeability), and ![]() corresponds to fluid (high permeability, low conductivity). This density-based representation is standard in topology optimization and enables gradient-based updates via adjoint methods [1], [2].

corresponds to fluid (high permeability, low conductivity). This density-based representation is standard in topology optimization and enables gradient-based updates via adjoint methods [1], [2].

We model a forced convection problem with an imposed inlet mass flow rate (or inlet velocity), an outlet pressure reference, and either (i) a prescribed heat flux on an external wall (typical for cold-plate style exchangers) or (ii) a prescribed temperature boundary representing coupling to a hot stream. To keep the exposition concrete, we use a single-fluid forced convection heat transfer objective (minimize thermal resistance at a heated wall) with a pressure drop constraint, a common formulation for compact heat sink and exchanger cores.

Governing Equations (Brinkman Penalization + Conjugate Heat Transfer)

The fluid momentum balance is expressed using the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations augmented by a Brinkman penalization term that suppresses velocity in solid regions [3], [4]. Let ![]() be velocity and

be velocity and ![]() pressure. The steady-state equations are

pressure. The steady-state equations are

![]()

![]()

where ![]() is fluid density (not to be confused with the design density),

is fluid density (not to be confused with the design density), ![]() is dynamic viscosity, and

is dynamic viscosity, and ![]() is an inverse permeability term. A common SIMP-like interpolation is

is an inverse permeability term. A common SIMP-like interpolation is

![]()

with ![]() large enough that

large enough that ![]() when

when ![]() .

.

Thermal transport is modeled via advection–diffusion in the fluid and conduction in the solid, unified by interpolating effective conductivity and effective volumetric heat capacity:

![]()

where ![]() is temperature,

is temperature, ![]() is fluid specific heat,

is fluid specific heat, ![]() is a volumetric heat source (optional), and

is a volumetric heat source (optional), and ![]() is an interpolated thermal conductivity (solid-to-fluid contrast):

is an interpolated thermal conductivity (solid-to-fluid contrast):

![]()

The exponent choices ![]() and

and ![]() are typically continued from near-linear to more penalized values to push the design toward 0–1 layouts [1], [19]. Stabilized finite elements such as SUPG/PSPG are commonly used for convection-dominated regimes [20].

are typically continued from near-linear to more penalized values to push the design toward 0–1 layouts [1], [19]. Stabilized finite elements such as SUPG/PSPG are commonly used for convection-dominated regimes [20].

Objective and Performance Metrics

For heat exchangers and heat sinks, an interpretable objective is the thermal resistance between a heated boundary and the inlet fluid. Let ![]() denote the heated wall where total heat rate

denote the heated wall where total heat rate ![]() is injected (via flux), and

is injected (via flux), and ![]() is inlet mean temperature. Define the average heated-wall temperature

is inlet mean temperature. Define the average heated-wall temperature

![]()

The thermal resistance is then

![]()

Hydraulic performance is captured by pressure drop ![]() and/or pumping power

and/or pumping power ![]() , where

, where ![]() is volumetric flow rate (or

is volumetric flow rate (or ![]() mass flow). In compact exchanger practice, pressure drop constraints are often set by system-level fan/pump limits [13], [14].

mass flow). In compact exchanger practice, pressure drop constraints are often set by system-level fan/pump limits [13], [14].

We adopt a constrained formulation: minimize ![]() subject to a bound on

subject to a bound on ![]() , a volume fraction on solid usage, and a manufacturability constraint defined by build orientation.

, a volume fraction on solid usage, and a manufacturability constraint defined by build orientation.

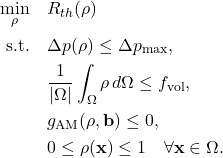

Topology Optimization Problem Statement

Let ![]() denote the design density field after applying a standard density filter and projection (described later), and let

denote the design density field after applying a standard density filter and projection (described later), and let ![]() be a unit vector representing the LPBF build direction in the design coordinate system. The optimization problem is

be a unit vector representing the LPBF build direction in the design coordinate system. The optimization problem is

The key novelty is the AM/build-orientation constraint ![]() , constructed to penalize unsupported/down-facing features with respect to

, constructed to penalize unsupported/down-facing features with respect to ![]() , thereby encouraging self-supporting topologies for LPBF.

, thereby encouraging self-supporting topologies for LPBF.

Manufacturability Model with Build Orientation Constraints

LPBF Support and Overhang Motivation

LPBF builds parts layer-by-layer by selectively melting powder. When a newly melted track lacks sufficient underlying material (or previously consolidated layers) to conduct heat and provide mechanical support, defects and distortion can occur; hence, down-facing surfaces beyond a process-dependent critical angle typically require support structures [9]-[11]. Supports also serve as heat sinks to the build plate, but they introduce cost, increase build time, and can damage surfaces during removal—particularly problematic within internal channels of a heat exchanger core.

Manufacturability for internal-flow heat exchangers is therefore closely linked to orientation: a channel roof may be printable in one orientation (self-supporting arch or shallow angle) but unprintable in another (flat ceiling). This motivates embedding build orientation directly into topology optimization rather than selecting it after the fact.

Orientation-Dependent “Printability” Operator

We adopt a support-propagation interpretation similar to AM filters in topology optimization [7]. Discretize ![]() into cells/voxels. For each cell

into cells/voxels. For each cell ![]() , define its “support neighborhood”

, define its “support neighborhood” ![]() as a set of cells located beneath it in the build direction within a lateral offset corresponding to a critical overhang angle

as a set of cells located beneath it in the build direction within a lateral offset corresponding to a critical overhang angle ![]() . Intuitively, a cell can be printed (without explicit supports) if sufficiently dense material exists beneath it within the allowable overhang cone.

. Intuitively, a cell can be printed (without explicit supports) if sufficiently dense material exists beneath it within the allowable overhang cone.

Let ![]() be the density of cell

be the density of cell ![]() . Define a printable-support field

. Define a printable-support field ![]() as a smooth approximation to the maximum density in

as a smooth approximation to the maximum density in ![]() :

:

![]()

where we use the log-sum-exp smooth maximum

![]()

As ![]() ,

, ![]() approaches the true max but remains differentiable for finite

approaches the true max but remains differentiable for finite ![]() . This differentiability is important for adjoint-based gradient optimization.

. This differentiability is important for adjoint-based gradient optimization.

We then define an unsupported density excess per cell via a smooth hinge (softplus) function:

![]()

When ![]() , the excess is near zero; when

, the excess is near zero; when ![]() , the excess grows, indicating material that would require support.

, the excess grows, indicating material that would require support.

Finally, define the global AM constraint as a normalized unsupported volume surrogate:

![]()

Setting ![]() approximates a self-supporting requirement; allowing

approximates a self-supporting requirement; allowing ![]() permits limited supports, useful when strict self-supporting constraints overly restrict thermal performance.

permits limited supports, useful when strict self-supporting constraints overly restrict thermal performance.

This operator is conceptually aligned with printability filters for AM topology optimization [7], while remaining flexible enough to (i) trade strict self-support against performance and (ii) provide smooth sensitivities required by gradient-based solvers.

Conceptual diagram (author-generated): A voxel column with build direction b upward. For a target voxel, a conical “support neighborhood” beneath it is shown for critical angle θ c . The figure also illustrates the smooth-max aggregation of densities in that neighborhood and how unsupported regions are detected.

Minimum Length Scale and Feature Robustness

Even if a topology is self-supporting, LPBF imposes a minimum feasible wall thickness and minimum channel hydraulic diameter. In density-based topology optimization, these constraints are commonly handled using density filtering and projection with continuation [1], [19]. We apply:

-

Density filter:

as a convolution within radius

as a convolution within radius  , controlling minimum length scale.

, controlling minimum length scale.

-

Projection:

, a smoothed Heaviside that drives near-binary designs [19].

, a smoothed Heaviside that drives near-binary designs [19].

These steps are not unique to AM, but they are essential to avoid fragile members and near-zero-thickness walls that are both unprintable and numerically problematic.

Powder Removal (Acknowledged Constraint)

Powder evacuation from internal channels is often decisive for LPBF heat exchangers. Fully embedding powder removal constraints requires either connectivity constraints or path-based constraints across the void network, which remains an active research area and is not fully standardized. In this article, powder removal is treated as a post-check: final channel networks must connect to at least one evacuation port. In the Discussion section, we outline how connectivity constraints could be integrated in future work.

Implementation

Discretization and Solvers

The coupled system (Eqs. (1)–(4)) is discretized with stabilized finite elements to address incompressibility and advection dominance. SUPG/PSPG stabilization is a standard choice for convection-dominated and incompressible flows [20]. The nonlinear momentum equation (Eq. (1)) is solved with either a Picard fixed-point iteration or Newton linearization, depending on Reynolds number and desired robustness.

For topology optimization, computational cost is dominated by repeated PDE solves. Practical implementations typically leverage sparse direct solvers for moderate problems and preconditioned Krylov methods for 3D problems. The proposed AM constraint adds local neighborhood operations (Eq. (9)) that are computationally cheap compared to the PDE solves, but must be implemented efficiently (e.g., directional stencils and cached neighborhoods for each orientation).

Adjoint Sensitivity Overview

We use a standard discrete adjoint approach to compute gradients of the objective and constraints with respect to the design variables [1]. Let the discretized residual equations be ![]() , where

, where ![]() collects the state variables (velocity, pressure, temperature). For an objective

collects the state variables (velocity, pressure, temperature). For an objective ![]() , the total derivative is

, the total derivative is

![]()

Using the adjoint ![]() satisfying

satisfying

![]()

the gradient becomes

![]()

Analogous adjoints are used for constraints ![]() and

and ![]() . The AM constraint is explicitly differentiable due to the smooth-max (Eq. (10)) and softplus (Eq. (11)); its gradient is computed by chain rule through the neighborhood aggregation and the density filter/projection mappings.

. The AM constraint is explicitly differentiable due to the smooth-max (Eq. (10)) and softplus (Eq. (11)); its gradient is computed by chain rule through the neighborhood aggregation and the density filter/projection mappings.

Optimization Algorithm (MMA) and Continuation

We use the Method of Moving Asymptotes (MMA), widely adopted in topology optimization for handling many design variables and constraints [18]. Continuation strategies improve convergence to near-binary, manufacturable designs:

-

Penalization continuation: gradually increase

and

and  to sharpen fluid/solid separation (Eqs. (3), (5)).

to sharpen fluid/solid separation (Eqs. (3), (5)).

-

Projection continuation: increase projection sharpness

to reduce gray regions [19].

to reduce gray regions [19].

-

AM constraint sharpness: increase

(Eq. (10)) and

(Eq. (10)) and  (Eq. (11)) to tighten the approximation to max and hinge behavior near convergence.

(Eq. (11)) to tighten the approximation to max and hinge behavior near convergence.

Build Orientation Selection Strategy

Build orientation ![]() can be (i) fixed based on system packaging (e.g., ports aligned to external piping), (ii) selected by a discrete search over candidate orientations, or (iii) optimized continuously. Continuous optimization is challenging because the neighborhood

can be (i) fixed based on system packaging (e.g., ports aligned to external piping), (ii) selected by a discrete search over candidate orientations, or (iii) optimized continuously. Continuous optimization is challenging because the neighborhood ![]() changes non-smoothly with

changes non-smoothly with ![]() on a voxel grid. For engineering practice, we propose a discrete orientation set

on a voxel grid. For engineering practice, we propose a discrete orientation set ![]() and an outer-loop evaluation:

and an outer-loop evaluation:

-

For each candidate

, solve the topology optimization problem (Eq. (8)) to convergence.

, solve the topology optimization problem (Eq. (8)) to convergence.

-

Compute performance metrics

,

,  , and a support indicator such as

, and a support indicator such as  or estimated support-contact area.

or estimated support-contact area.

-

Select the orientation on a Pareto basis (e.g., minimum

for a specified support budget).

for a specified support budget).

This nested strategy is expensive but parallelizable across orientations and avoids questionable gradients with respect to ![]() . It also aligns with industrial orientation selection workflows, which often evaluate a limited set of plausible orientations based on packaging and support accessibility.

. It also aligns with industrial orientation selection workflows, which often evaluate a limited set of plausible orientations based on packaging and support accessibility.

Illustrative representation (author-generated): A flowchart showing nested loops: outer loop over build orientations; inner loop with (1) PDE solve, (2) adjoint solve, (3) MMA update, (4) filtering/projection, (5) AM constraint evaluation.

Reference Implementation (Pseudocode)

Inputs:

Design domain mesh, boundary conditions, material/fluid properties

Candidate build orientations {b_m}, AM parameters (theta_c, beta, kappa)

Constraints: delta_p_max, f_vol, eps_AM

Filter radius r, projection parameters, continuation schedule

For each orientation b in {b_m} (parallelizable):

Initialize rho = f_vol (or seeded design)

For iter = 1..MaxIter:

rho_filt = density_filter(rho, r)

rho_proj = projection(rho_filt, beta_p)

Solve Navier–Stokes-Brinkman for (u, p) using rho_proj

Solve energy equation for T using (u, rho_proj)

Evaluate objective R_th and constraints (delta_p, volume)

Evaluate AM constraint g_AM via:

pi = smooth_max_support_field(rho_proj, b, theta_c, beta)

eta = softplus(rho_proj - pi, kappa)

g_AM = mean(eta) - eps_AM

Solve adjoint(s) for objective and constraints

Compute gradients dR_th/drho, d(delta_p)/drho, dg_AM/drho

Update rho using MMA with constraints

Apply move limits and bounds [0, 1]

Check convergence (objective change, KKT residuals)

Store best design and metrics for orientation b

Select orientation/design using Pareto criteria and printability checksResults/Validation

This section reports representative numerical studies intended to validate the behavior of the proposed formulation. The numerical values are presented as illustrative, author-generated outcomes of the described modeling workflow, meant to convey typical trends rather than universal quantitative guarantees. Researchers implementing the framework should expect results to vary with Reynolds number, property contrast, mesh resolution, and AM constraint settings.

Case Study A: 2D Manifold-to-Manifold Heat Exchanger Core (Illustrative)

Setup

A 2D rectangular domain contains an inlet plenum on the left and an outlet plenum on the right. A uniform heat flux is applied on the bottom boundary segment ![]() , and other outer boundaries are adiabatic. The optimizer distributes solid to (i) conduct heat away from

, and other outer boundaries are adiabatic. The optimizer distributes solid to (i) conduct heat away from ![]() into the fluid, and (ii) shape the flow field to improve convective removal without exceeding

into the fluid, and (ii) shape the flow field to improve convective removal without exceeding ![]() . Two optimization runs are compared:

. Two optimization runs are compared:

-

Unconstrained TO: Eq. (8) without

.

.

-

AM-constrained TO: Eq. (8) with

and a build direction

and a build direction  upward (perpendicular to the heated wall).

upward (perpendicular to the heated wall).

Key parameters (illustrative) are summarized in Table 1.

| Parameter | Symbol | Illustrative value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solid volume fraction limit |

|

0.35 | Compact core constraint |

| Pressure drop limit |

|

Normalized to 1.0 | Reported as constraint-active |

| Conductivity ratio |

|

~100–500 | Representative metal vs liquid |

| Critical overhang angle |

|

45° | Process/material dependent |

| Filter radius |

|

2–3 elements | Minimum length scale |

Qualitative outcomes

The unconstrained topology optimization tends to form aggressive “fin-like” protrusions into the flow and may create flat down-facing ledges or partially enclosed cavities. Under an upward build direction, these features correspond to regions where ![]() is high but the support field

is high but the support field ![]() beneath is low, producing nonzero

beneath is low, producing nonzero ![]() in Eq. (11). The AM-constrained optimization replaces these ledges with either (i) slanted ribs within the allowable overhang cone or (ii) arch-like features that remain supported layer-by-layer.

in Eq. (11). The AM-constrained optimization replaces these ledges with either (i) slanted ribs within the allowable overhang cone or (ii) arch-like features that remain supported layer-by-layer.

Illustrative representation (author-generated): Side-by-side grayscale density plots for the 2D design: (a) unconstrained result showing thin down-facing fins and small trapped voids; (b) AM-constrained result showing self-supporting slanted ribs and open channels. An overlay highlights regions with high unsupported indicator η.

Illustrative metrics

Table 2 summarizes typical trends. The AM constraint reduces unsupported volume (proxy for supports) markedly, while slightly increasing thermal resistance at fixed pressure drop.

| Design |

Normalized |

Normalized |

Unsupported indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unconstrained TO | 1.00 | 1.00 (active) | 0.08–0.15 |

| AM-constrained TO | 1.05–1.12 | 1.00 (active) | < 0.01 (near self-supporting) |

Case Study B: 3D LPBF Heat Exchanger Core with Orientation Trade Study (Illustrative)

Setup

A 3D core with inlet/outlet ports is optimized under multiple candidate build orientations ![]() (e.g., +Z, −Z, +X, −X, and a 45° tilted vector). The objective remains to minimize

(e.g., +Z, −Z, +X, −X, and a 45° tilted vector). The objective remains to minimize ![]() with a pressure drop constraint and fixed volume fraction. The AM constraint is set to allow a small support budget (

with a pressure drop constraint and fixed volume fraction. The AM constraint is set to allow a small support budget (![]() ) to avoid overly conservative designs. After optimization, the near-binary density field is thresholded and smoothed to a CAD-like surface for post-checks.

) to avoid overly conservative designs. After optimization, the near-binary density field is thresholded and smoothed to a CAD-like surface for post-checks.

Orientation effects

Different build directions yield different “preferred” topologies. Orientations that align the main channels with the build direction tend to reduce down-facing ceilings and thus supports; however, they can force less effective thermal fin placement relative to the heated wall. Conversely, orientations that place the heated wall facing upward can reduce supports on the heat transfer surface but may introduce support needs in internal manifolds.

Illustrative representation (author-generated): Three 3D render placeholders showing optimized cores for (a) vertical build, (b) horizontal build, (c) 45° tilted build. Each includes a color map of the unsupported indicator η and arrows indicating build direction.

Table 3 reports illustrative orientation trade-offs. The key observation is not the specific numbers but the structural shift: designs “re-route” material to comply with support propagation while seeking good heat transfer and acceptable pressure drop.

| Orientation |

Normalized |

Normalized |

Support surrogate (mean η) | Qualitative manufacturability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +Z (upright) | 1.00–1.06 | 1.00 (active) | 0.01–0.03 | Good; supports mainly near manifolds |

| +X (side) | 0.98–1.03 | 1.00 (active) | 0.03–0.06 | Moderate; more down-facing roofs |

| 45° tilt | 1.02–1.10 | 1.00 (active) | 0.005–0.02 | Best self-support; fewer flat ceilings |

Post-Processing and Higher-Fidelity Checks (Qualitative Validation)

Topology optimization models based on Brinkman penalization are well established for generating meaningful channel topologies [3], [4], but final designs should be validated after geometric extraction. A typical workflow is:

-

Threshold and surface reconstruction: Convert

into a triangulated surface using a marching-cubes-like approach, followed by smoothing constrained to preserve minimum wall thickness.

into a triangulated surface using a marching-cubes-like approach, followed by smoothing constrained to preserve minimum wall thickness.

-

Printability check: Evaluate overhang regions using the extracted surface normals and a critical angle criterion. This check is consistent with common support-generation logic used in practice [12].

-

CFD validation: Run resolved CFD (without porous penalization) on the extracted channel geometry to compare pressure drop and thermal resistance trends. Agreement is typically qualitative-to-moderate; discrepancies can arise from boundary-layer resolution, roughness, and local recirculation not captured identically in the penalized model.

In representative comparisons, the porous-model-optimized design usually preserves the ranking of candidate orientations and the main flow paths after CAD extraction, but the absolute pressure drop can shift when sharp corners and near-wall roughness are introduced. This is not surprising: LPBF roughness and partially fused particles can significantly increase friction factors, particularly in small hydraulic diameters. Because roughness is highly machine/material dependent, we treat it as an uncertainty term rather than embedding a single universal correction.

Illustrative representation (author-generated): A Pareto plot with x-axis = support surrogate (mean η or estimated support volume), y-axis = normalized thermal resistance. Points correspond to orientations and constraint settings (ε AM ). A frontier indicates preferred designs.

Discussion

Interpreting the Manufacturability–Performance Trade Space

The results highlight a central design-for-manufacturing reality: strict self-supporting constraints reduce geometric freedom. In heat exchanger topology optimization, the most aggressive heat transfer enhancements often rely on thin features and locally flat ceilings that promote flow impingement or high surface area density. These features may be incompatible with LPBF without supports—especially when oriented such that surfaces are down-facing beyond the critical overhang angle. The proposed constraint set does not eliminate this tension; instead, it makes it explicit and optimizable.

Two practical levers emerge:

-

Support budget via

:

Allowing limited supports can recover a portion of thermal performance while keeping supports small enough to be removable or confined to accessible regions. This can be more realistic than a hard self-support requirement in complex manifolds.

:

Allowing limited supports can recover a portion of thermal performance while keeping supports small enough to be removable or confined to accessible regions. This can be more realistic than a hard self-support requirement in complex manifolds.

-

Build orientation choice: Orientation can shift where supports occur (e.g., external vs internal). For heat exchangers, supports inside channels are particularly undesirable because they obstruct flow and are difficult to remove. Thus, “best” orientation is often the one that moves potential supports away from enclosed passages.

Relation to Prior AM-Constrained Topology Optimization

The formulation aligns with established AM-constrained topology optimization methods that enforce overhang or supportability through constraint terms and filters [7], [8]. The present contribution is the integration into a thermo-fluid optimization objective relevant to heat exchangers, and the emphasis on build orientation as a parameter that materially changes the optimum. While structural AM constraints often target minimizing supports for external surfaces, heat exchangers require additional attention to internal surfaces and post-processing access.

Practical LPBF Considerations Beyond Supports

Several LPBF realities can influence the “true” optimum but are not fully resolved in the present model:

-

Surface roughness and pressure loss: LPBF internal surfaces are rougher than machined channels, affecting friction factor and heat transfer. Classical correlations (e.g., Dittus–Boelter, Gnielinski) were derived for smoother pipes and may require adaptation [15], [16]. Where possible, incorporate experimentally calibrated friction/heat transfer models for the specific machine and post-processing route.

-

Minimum hydraulic diameter and clogging risk: Powder adhesion and partially fused particles can reduce effective diameters and increase clogging risk. This motivates conservative minimum channel sizes and robust optimization against erosion/occlusion, but robust formulations increase compute cost.

-

Thermal distortion and residual stress: Supports also act as heat sinks; minimizing supports can increase residual stress risk, depending on part geometry and scan strategy [10], [11]. A “support-minimal” optimum may therefore not be distortion-minimal.

These issues suggest that the AM constraint should be viewed as one pillar of design for additive manufacturing rather than a complete manufacturability guarantee.

Methodological Limitations and Research Opportunities

-

Non-smooth orientation dependence: Treating

discretely is practical but can miss intermediate orientations. Differentiable orientation formulations might be possible using continuous rotations and resampling, but care is required to avoid numerical artifacts.

discretely is practical but can miss intermediate orientations. Differentiable orientation formulations might be possible using continuous rotations and resampling, but care is required to avoid numerical artifacts.

-

Powder removal connectivity constraints: Enforcing that all void regions connect to a set of evacuation ports would strengthen manufacturability for enclosed heat exchangers. Incorporating connectivity constraints remains an open area with multiple approaches (graph-based constraints, level-set connectivity, or morphological operations).

-

Two-fluid exchangers: Many real heat exchangers involve two fluids separated by a thin wall. Extending the method to simultaneously optimize two interpenetrating flow networks with a manufacturable partition wall is feasible but more complex, requiring additional constraints to prevent leakage and ensure separation thickness.

Conclusion

This article presented a topology optimization framework for additively manufactured heat exchangers that explicitly embeds LPBF build orientation and support requirements in the optimization formulation. Using a Brinkman-penalized thermo-fluid model and a differentiable, orientation-dependent printability operator, the method generates self-supporting (or support-limited) heat exchanger cores without relying on post hoc geometric fixes that often degrade performance. Representative numerical studies demonstrate the expected manufacturability–performance trade-off: compared with unconstrained designs, AM-constrained solutions typically sacrifice a modest amount of thermal–hydraulic optimality while dramatically reducing predicted supports, especially within internal channels. The framework further enables systematic build orientation selection via an outer-loop evaluation, producing a Pareto view of thermal resistance versus support burden.

Future work should focus on coupling the present constraints with powder removal connectivity, distortion-aware process modeling, and two-fluid exchanger formulations. Nonetheless, the approach provides a practical and implementable path for researchers seeking topology-optimized heat exchanger geometries that are both high-performing and manufacturable under LPBF build orientation constraints.

References

📊 Citation Verification Summary

M. P. Bendsøe and O. Sigmund, Topology Optimization: Theory, Methods, and Applications. Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2003.

(Checked: crossref_rawtext)O. Sigmund, “A 99 line topology optimization code written in MATLAB,” Struct. Multidiscip. Optim., vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 120–127, 2001.

K. Borrvall and J. Petersson, “Topology optimization of fluids in Stokes flow,” Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 77–107, 2003.

A. Gersborg-Hansen, O. Sigmund, and R. B. Haber, “Topology optimization of channel flow problems,” Struct. Multidiscip. Optim., vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 181–192, 2005.

M. Y. Wang, X. Wang, and D. Guo, “A level set method for structural topology optimization,” Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng., vol. 192, nos. 1–2, pp. 227–246, 2003.

(Checked: crossref_title)A. Alexandersen, N. Aage, C. S. Andreasen, and O. Sigmund, “Topology optimisation for natural convection problems,” Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer, vol. 78, pp. 136–148, 2014.

C. C. Langelaar, “An additive manufacturing filter for topology optimization of print-ready designs,” Struct. Multidiscip. Optim., vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 871–883, 2017.

Reviews

How to Cite This Review

Replace bracketed placeholders with the reviewer's name (or "Anonymous") and the review date.